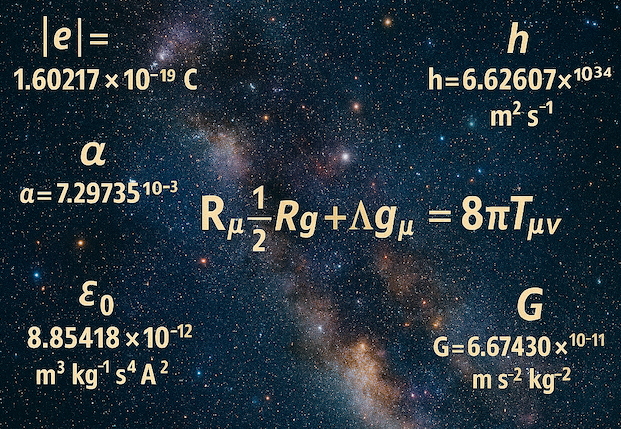

Impossible odds based on Universal Constants

The Improbable Universe: Why Chance Can't Explain the Fine-Tuning for Life

SCIENTIFIC

12/8/20254 min read

In the vast expanse of cosmology, one of the most profound questions is why our universe seems perfectly suited for life. From the formation of stars and planets to the existence of complex chemistry, everything hinges on a set of fundamental constants—numbers that govern the laws of physics. These constants, such as the strength of gravity or the speed of light, appear to be exquisitely "fine-tuned." If they were even slightly different, life as we know it—and possibly any form of life—could not exist. This article explores why a universe capable of supporting life would be statistically impossible if these constants arose purely by random chance.

What Are Universal Constants?

Universal constants are the fixed values in the equations of physics that describe how the universe works. They include things like the gravitational constant (G), which determines the pull of gravity; the strong nuclear force constant, which holds atomic nuclei together; and the cosmological constant, which influences the expansion of the universe. These aren't arbitrary numbers we can change; they're baked into reality.

Scientists have discovered that these constants must fall within incredibly narrow ranges for the universe to produce stars, galaxies, planets, and the building blocks of life like carbon and water. This phenomenon is known as "fine-tuning." The key argument is that if the universe originated from random processes—say, a multiverse where constants vary wildly from one bubble to another—the odds of getting our exact set are so minuscule that it's effectively impossible.

The Cosmological Constant: A Razor-Thin Balance

The cosmological constant governs the rate at which the universe expands. It's an incredibly small number: about 1.2 × 10^{-123} in natural units. If it were just a few orders of magnitude larger, the universe would expand too rapidly for galaxies and stars to form—everything would be a diffuse gas with no clumping of matter. If slightly negative, the universe would collapse back on itself shortly after the Big Bang, before any complex structures could emerge.

In essence, 1 × 10^{-123} is so small that events with this probability are effectively impossible in our universe's lifetime or volume — it's a number that highlights the extremes of both mathematics and physics.

The Strong Nuclear Force: The Glue of Atoms

The strong nuclear force binds protons and neutrons in atomic nuclei. If it were 2% weaker, multi-proton nuclei couldn't form, leaving the universe filled only with hydrogen—no heavier elements like carbon or oxygen for life. If 2% stronger, all hydrogen would convert to helium early on, eliminating water and stable stars.

This force is 10^40 times stronger than gravity, but its value relative to other forces must be precise within a narrow window. Even a 50% deviation could halt stellar nucleosynthesis, the process in stars that creates essential elements. The odds of this exact strength emerging randomly? Astronomically low, especially when combined with other constants.

Gravity and the Weak Force: Building Blocks of Stars

The gravitational constant must be balanced against the weak nuclear force and others. If gravity were slightly stronger relative to electromagnetism, stars would be smaller and burn out too quickly for life to evolve. If weaker, stars and planets wouldn't form at all. Similarly, a change in the weak force by a factor of 10 would lead to too many neutrons in the early universe, preventing hydrogen-burning stars like our Sun.

One estimate puts the fine-tuning of gravity and the weak force at 1 part in 10^50 for maintaining the universe's structure against the cosmological constant.

The Initial Low-Entropy State: Order from Chaos

Beyond constants, the universe started in an extraordinarily low-entropy (highly ordered) state. If it began in high entropy, energy would be too spread out for stars or life to form. Physicist Roger Penrose calculated the odds of this low-entropy beginning as 1 in 10^{10^{123}}—a number so vast it's beyond comprehension. This isn't a constant per se, but a "brute fact" of the universe's initial conditions, making random chance even more implausible.

The Statistical Impossibility of Chance

Now, imagine all these factors aligning perfectly by pure luck. It's not just one constant; it's dozens, each with razor-thin margins. Multiplying the probabilities—10^{-120} for the cosmological constant, 10^{-50} for gravity, and the mind-boggling 10^{-10^{123}} for entropy—yields a combined likelihood so small it's effectively zero.

To put it in perspective: The number of atoms in the observable universe is about 10^80. The odds here dwarf that by exponents upon exponents. If the universe's constants were set randomly, the chance of getting a life-permitting one is like picking a single specific atom from trillions of universes, blindfolded, on the first try.

Naturalistic explanations, like an infinite multiverse where every possible constant exists somewhere, attempt to sidestep this. But this just complicates the question of why matter or a universe exists at all, the more complicated the "explanation" get, the more likely, a creator was involved.

Conclusion: Beyond Randomness

These are just a just a few examples of the existing constants that govern our universe, there are many more (26 currently know dimensionless parameters) which adds to the incredibly small odds of our universe popping into existence from nothing with the exact constants to support life. The fine-tuning of our universe screams design, not accident. Tiny modifications to these constants would yield a barren, lifeless cosmos—no stars, no chemistry, no us. Statistically, a random universe supporting life is essentially impossible.

Contact

Questions or thoughts? Reach out anytime.

info@lifeanswers.me

© 2025. All rights reserved.